Intersex, people born with characteristics that do not mark them as male or female, will not count during the ongoing national population census. The intersex group will be counted among male or female gender markers, losing another opportunity for the country to specifically plan for them, which could have gone a long way in fighting stigma and discrimination against intersex persons. The Uganda National Population and Housing Census 2024, which is underway, started on May 9 and will enumerate people for 10 days, ending this Sunday, May 19.

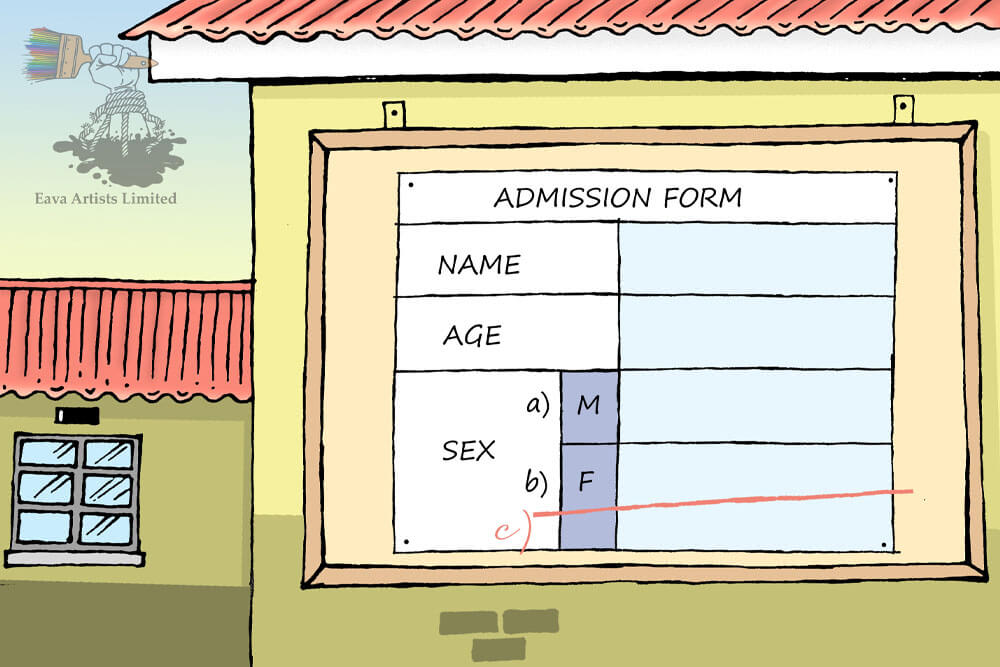

“Our questionnaire reads only male and female. This is because our laws do not recognise the intersex. We only consider males or females,” Didacus Okoth said, the senior public relations officer of the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS).

Okoth, who acknowledges the existence of intersex, said the bureau developed the questionnaires according to the legal jurisdiction. “We know the intersex exist, but Parliament has never discussed or recognised them by passing any law. But within us, communities may have such people,” he said.

Okoth added the bureau held consultative meetings, but none brought out the question of the intersex living in the community. “When we were developing the questionnaire, we had consultative meetings with researchers, academia, civil society, and religious leaders so that we do not leave anybody behind. If the issue of the intersex people didn’t come up, we cannot implant it in the questionnaires,” he argued.

In Kenya, during their last census of 2019, they introduced the third marker of intersex and counted 1,524 intersex persons, a first for an African country. Intersex people are born with sex characteristics (such as sexual anatomy, reproductive organs, hormonal patterns, and/or chromosomal patterns) that do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies, the UN estimates that up to 1.7 percent of the world population are born with intersex traits. Two years ago, Kenya amended the Children’s Act 2022, recognising and protecting the intersex. “An intersex child shall have the right to be treated with dignity, and to be accorded appropriate medical treatment, special care, education, training consideration as a special need category in social protection services,” the Act reads, in part.

Even though the intersex people are not on the questionnaire, experts said UBOS could still salvage the situation by recording the category in ways they can be recognized by law in the future.

“The intersex people have a right to be counted, they have a right to feature in the national statistics. How about if data comes with such people, how do we capture it? It is not too late because we can include those indicators probably when we are tallying the data at the national level. It will help have a clear picture of how many intersex people are in the country,” Dr Ben Kibirige, a sexual and reproductive health and rights expert said.

Dr Kibirige said UBOS, as a government agency, is indeed in an advantageous position to gather all sorts of available data that could prompt policies and laws for the intersex Ugandans.

“Whatever data they get, it is for policy streamlining. If that data is obtained, it will inform other agencies. If they realise that we have people who are intersex, that can trigger more discussions on issues people were arguing about using emotions. If we attach numbers to those arguments, even if you are a policy maker, implementor, or implementing partner, you realise intersex people truly exist. Meaning we are supposed to plan, create, and deliver services to them too,” he argued.

Stories of stigma, discrimination

Statistics on the numbers of intersex are scanty because many parents hide the information. Many African parents consider intersex children as a bad omen. A baby is born intersex due to hormone abnormalities during pregnancy which interrupt the formation of a fetus’ sex organs and random differences in chromosomes that occur during conception.

Jessy, who was born with small male genitalia, broke down as she narrated the suffering her mother went through as she raised her.

Jessy, now a young adult was shocked to find other intersex people. “I never knew there were others like me,” she said when she was taken under the care of the Support Initiative for People with Congenital Disorder (SIPD), an intersex rights and health organisation.

“My prayer or heartfelt desire is for a successful intersex surgery. I want to tell the intersex children: ‘Stop self-discrimination and self-stigmatisation. Be who you are. Stand up and raise your issues. You will always be a child of God – no matter what,”

SIPD’s Tom Makumbi said some people relate being intersex to homosexuality yet the two are different.

“My vision is to see a stigma-free environment where intersex persons fully enjoy their rights and dignity like any other person in the country. I want to see an empowered intersex community,” Karol, an intersex activist, said.

Children born as intersex can undergo surgery for treatment and correction. For instance, if the characteristics of intersex are two physical reproductive organs (vagina and penis), the surgery correction is by removing the inactive part, leaving the person with the dominant one. Parents usually give consent on the baby’s behalf, but human rights activists believe the consent should be given by the intersex person. “Different ages and levels come with different complications. And what is needed to correct something is always different in terms of ages and infrastructure,” Kibirige, a medical doctor, said concerning the need for therapy at appropriate times. The other challenge is fully ascertaining which characteristics are accurately dominant, the reason activists advocate that surgery is done at least after adolescence when one is an adult.

Dr Kibirige said therapy should embrace human rights. “If you are in the full principles of human rights, we would wish the person you are doing the procedure on has full understanding on that. It should not be forced on people. It should be a choice taken by an individual after fully knowing the pros and cons of the procedure,” he advised.

Surgeries can be done in the country, especially at Mulago Hospital, but the success rate generally is low largely because of insufficient equipment.

Uganda’s population was 34.6 million in 2014. It is now estimated to be over 47 million, but hundreds of Ugandans who are intersex will neither count nor be counted in their capacities. Yet, one of the objectives of the census is to ‘offer key data for national initiatives and supports special interest groups for improved social protection’.